1. Sheng, Jew's harp and the spirit of the ageThe concertina, bandonion and accordion form the instrument family of the hand harmonicas (squeezebox). Their sound production, like that of the harmonica, is based on free reeds, which are already known from two very old instruments: the since more than 3.000 years in China and Southeast Asia used mouth organ Sheng and the in many cultures used Jew's harp. The latter is proven in Europe until Celtic-Roman times. A free reed oscillates periodically through the surrounding oscillation channel (frame) of the reed plate. The pitch depends on the dimensions and weight of the reed, which determine the vibration speed (reed principle). In contrast, a beating tongue periodically beats on its frame without swinging freely through it. Its volume is amplified by an adjoining resonance chamber, a tube as in clarinet, oboe and saxophone, in which the blown reed, excites the air in the tube to vibrate. Pipes also amplify their sound with an air-filled tube, but the vibrations are generated by blowing on an edge (e.g. flute, organ pipe). The reeds of the Sheng were learned by the physicist C.G. Kratzenstein from Wernigerode in St. Petersburg. He used this type of sound generation in his experiments on the artificial generation of speech sounds beetween 1770-80. Around 1780, thanks to Kratzenstein's experiments and findings, an assistant Russian organ builder Kirschnigk (or Kirsnik) began to build keyboard instruments with free reeds. The German composer G.J. Vogler (a teacher of Carl Maria von Weber) is said to have learned to use these instruments on a trip to Russia, and then introduced the percussion reeds into organ building in Germany (e.g. in 1792 at the organ of the Carmelite monastery in Frankfurt am Main). Organs had been built for a long time (even in small portable sizes as portatives and shelves), but the sound of a single pipe could not be made dynamic. Only on larger organs was it possible to change the volume at least gradually by combining several pipes to form choirs or by opening and closing sound covers. The new sound ideal around 1800, however, was the singing tone, which was supposed to be changeable in volume and duration, as it were, as an expression of feelings, as in singing and violin. In contrast to the previously popular but static sounding lute and the harpsichord, now the swelling and declining of a tone delighted the listener. In this way, the spirit of the times promoted the spread of the free reed (in german also known as the tone-feather), first as an additional voice in organs, then in 1810 in the Aeoline of Eschenbach and Schlimmbach in Bad Königshofen, in 1821 in Anton Haeckel's Physharmonika in Vienna, until the instrument of the French organ builder Debain (1842), which was first called the Harmonium. These, as well as other unnamed developments, are comparable to today's pianos in appearance and were supplied with wind by a pedal bellows. Some of these instruments, such as the Physharmonika, were already produced in small, arm-sized models, on which one hand played and the other operated the bellows. The spread of another musical instrument with free reeds also occurred during this period - the mouth harmonica. Around 1825 this instrument was already in great demand. Initially equipped with only a few notes and attached to walking sticks and similar everyday objects, it was, however, in its early days more of a curious toy than a musical instrument. Before the first hand harmonicas were invented, free reeds had already led to two different new types of instruments: the harmonica variants oriented to piano and organ and the wind instrument mouth harmonica. |

|

2. Hand harmonicas, who invented them?In order to establish the family of hand harmonicas (hand pull bellows instruments), it took two changes to the hand organs (portativs) which have been in use for a longer time. Firstly, free reeds had to replace the pipes that had been used up to then. Shortly after 1800 this was done with Aeoline and Physharmonika. Secondly, the previously separate instrument parts: manual, sound generators and bellows fuse into one unit. This way the movement of the bellows into the making music can be integrated, so that it must no longer be operated with one hand, a second person or pedals were needed. Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann from Friedrichsroda in Thuringia, son of a instrument maker, took a decisive step in this direction in 1822. Bushman had already built a mouth aeoline with several reeds which he called an Aura and how a harmonica was blown on. He provided this Aura with valves and connected it to a bellows, so that the wind pressure could be used to produce the tones. Since the keys and the bellows now formed a structural unit, they could be operated with one hand. The already long known bellows instruments portativs and shelves with so far separated key and bellows operation (one hand or with an assistant on the bellows), could be adapted according to this principle to new types of hand pull instruments. These made it possible to design the single tone and thus a contemporary expressive play by the use of free reeds. Buschmann called his development Handaeoline, soon also Concertina. The members of the Buschmann family were not only instrument makers, but also lecturers, who on their many concert tours through Europe also brought their latest developments with them and made them public. Imitations and further developments of their ideas were not long in coming. At the same time Anton Haeckel in Vienna 1821 succeeded in making a decisive improvement in free reeds. He fixed it asymmetrically to its frame, not as usual centrally in the vibration frame, but on one side of the reedplate. His patent concerned "...thin leaves attached at one of their ends to a brass plate which is attached to the sheets of the same cut-out...". Although these reeds (in contrast to the from Sheng and Jew's harp copied) only at one wind direction, but with a sound quality and volume never achieved before. He built these new reeds in the reed system of his designed Physharmonika, a piano-like pressure wind instrument with pedal operation of the bellows. Its asymmetrical reed attachment quickly became standard. The development thus includes various innovations of several resourceful minds, which together made the new family of hand harmonicas possible. |

|

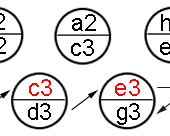

3. Cyrill Demian (Wien) and Charles Wheatstone (London).Following Bushman's key idea, Cyrill Demian and Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875) developed hand harmonikas, which were quite different in their purpose. Demian applied for a patent for an Accordion in Vienna and offered the buyers of his first model five bisonoric keys for the left hand (the right hand operated the bellows), with five prefabricated chords (multi-tones: three major and two seventh chords) could be played. Wheatstone built a Concertina in London in 1833 with 24 keys of the same tone distributed to both hands - all single tones, which in contrast to Demian's diatonic tone supply, have a chromatic tone sequence. The instrument was conceived as a melody instrument and should compete with the violin. Demians Accordion, on the other hand, was for the harmonic chord accompaniment thought of singing. So a melody instrument and a chord instrument were developed separately - both in one will follow shortly afterwards. But already here at the beginning of the development there are the two different constructions: bisonoric and unisonoric. |

4. Why were the first hand harmonicas bisonoric?By shifting the reeds into the bellows, wind can now be used in two ways to stimulate the tongues: when the bellows are pulled apart inflowing and when squeezing it outflowing wind. The reeds are in chambers (channels) made of wood, whose wind supply is controlled by the keys. Are two tongues of different pitch are installed in a chamber of a key in such a way, that one for pressure wind and the other for suction wind, two different tones can be called up with one key. The tone changes depending on the direction of movement of the bellows - the key has a different tone occupied. If this applies to the majority of keys, an instrument is called bisonoric. This construction method does not arise from musical requirements, but enables a cost-effective manufacture, because a tone range can be accommodated in the smallest of space with the smallest possible number of keys and the following mechanism, because two different tones require only one key mechanism and one chamber. But each tone should be playable for both bellows directions would require twice the number of reeds, chambers and keys. Which would mean a higher price for the buyer but not a larger tone range. Especially the reedplates with tongues are a considerable cost factor due to their complex production. Their machine production only succeeded from 1878 (Graf, p.114). Cyrill Demian used this economic advantages in the development of its accordion, also because it is responsible for the playability of chords meant no restrictions. On the contrary, practical for the game was the changing Assignment of the chord keys with frequently occurring harmony sequences. Cyrill Demian used this economic advantages in the development of its accordion, also because it meant no restrictions for the playability of chords. On the contrary, practical for the game was the changing disposition of the chord keys with frequently occurring harmony sequences. For example, with only one key pressed, the dominant and tonic are simply played. For the most common harmonic final turn, the finger can remain on the same key and only the bellows movement had to be changed. |

|

5. The English Concertina from LondonCharles Wheatstone in London built unisonoric hand harmonicas from the very beginning. His instrument, patented in 1829 and later called Concertina, produces the same note on one key in both bellows directions. The tone assignment is alternating sides, i.e. the tone sequence of a scale alternates continuously between the left and right manual (which Wheatstone had adopted from his earlier Symphonium, a wind (mouth) instrument with reeds). The two manuals cannot be played independently of each other, which is why self-accompaniment is not possible. Wheatstone's Concertina is a pure melody instrument, as it was intended to measure itself against the violin. By opting for the unisonoric principle, Wheatstone made it possible to play independently of bellows changes, in contrast to Uhlig's later Deutsche Konzertina. With the chromatic tonal stock, all keys could be played, while Uhlig's first diatonic Konzertinas were limited to 1 or 2. But with them a bass or chord accompaniment of the melody was possible, even if the manuals were only partially independent due to the bellows dependency. Wheatstone and others later attempted to remove the limitations on alternating sides tonal assignment by means of a Duet Concertina. 'Duet' means that with two independent manuals the "concertina can play duet with itself", i.e. an independent accompaniment is possible. The first successful keyboard system for this was patented decades later in 1884 by the young musician Maccann. The English Concertina (as a generic term for unisonoric concertinas) has always been a product of high quality and price, if only because of the larger number of reeds as a result of the unisonoric construction. Musical considerations took precedence over cost issues at Wheatstone.

|

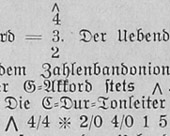

6. C.F. Uhligs Deutsche Konzertina (German Concertina) from Chemnitz in SaxonyThe manufacturing centre of the early instruments with free reeds was Vienna. Mouth harmonicas, the Physharmonika and also the first Accordion were made by instrument makers of this city. Through trade these instruments reached other regions and were copied there or used as inspiration for own developments. Around 1830 Carl Friedrich Uhlig (1789-1874), who played the clarinet, occupied himself as instrument maker in Chemnitz with the improvement of the Handaeoline of C.F. Buschmann and the Accordion from C. Demian. His square instrument, which he called the Concertina, initially had five bisonoric keys of a key on both sides. However, there were no prefabricated chords (as was already the case with C.F. Buschmann), but only single notes, which in contrast to Demian's Accordion means the branch of Deutschen Konzertina. The single tones were only available in one bellows direction (either tension or compression), because only one reed was built into each tone. Already around 1836 the range was increased to 40 tones (10 bisonoric keys on each side) and included two keys in two identically constructed rows, e.g. C and G major. This first enlargement of his Concertina became three repeat tonesto play tones in both bellows directions. Uhligs 20- and 40-tone Concertina with one or two keys were suitable for folk music, but due to the bisonoric principle, it is hardly possible to go beyond this. Because playing through notes, holding, ornaments (trill, mordent), follow up, or fast scale passes, everything that requires fast second steps is not possible at all or only with difficulty playable due to the necessary bellows changes. And if a chord is played on the left side, only melody notes in the same bellows direction can be played on the right. The manufacturers therefore soon built larger instruments with 88, 108 or 130 tones (before 1868). The constant increase of the tone range was firstly the aim of enlargement of the tone range. On the other hand, repeat tones (tone doubling) were built in for play independent of the bellows directions. But against the trend and despite the sales success of the competition with larger instruments, Uhlig refused to build his Concertina with more than 76 notes (Graf S.174). For a long time, it therefore had a smaller range of sounds than its competitors, but on the other hand it had a comparatively less complex keypad than larger instruments. At the end point of these tone expansions, which were carried out over decades, almost all tones were doubled. The original advantage of the bisonoric construction, the saving of reeds, mechanism and the resulting low-cost production, was eaten up by the need for a larger tone range. The development ultimately led to two reeds for each tone, as was the case decades earlier has been common practice at Wheatstones Double Concertina from the very beginning. However, these two reeds in same pitch were not assigned on a common button, as in Wheatstone within its consistently systematic keyboard system, but in their overwhelming majority, spread over two in line with changing priorities. At the beginning of the development of models with only 10 keys, instruments with up to over 70 keys and the resulting complexity not foreseeable. Although with tone expansions and repetition tones the described musical limitations as far as possible have been overcome, but only at a significant cost to learners: at this path of development, a tone (dis)order was established in complete contrast to a spatially logical, systematically structured keyboard system. This circumstance should today be a major reason why there is not much interest in learning this instrument in Germany. A keyboard with bisonoric tones follows the logic of the favourable grip as far as possible. However which tones are hidden behind which key, cannot be logically deduced by the learner except in a small core area, but requires an (actually unnecessary) extremely high learning effort for the orientation on the keyboard alone. Four different tone arrangements are to be learned: manual on the left and right side - each for push and pull different, without a musical advantage compared to an unisonoric instrument. That despite the ever-increasing complexity of the following tone enhancements, the bisonoric principle was further maintained is probably best explained by the fact, that the buyers of the first Konzertinas with small tone stock was also considered a potential customer for the following expanded models. Every tone extension had to take into account their learned playing skills, what excluded a change from the once established keyboard system. Generally speaking, a path dependency arises. A reproduction mechanism that matches the initial investment and benefits of manufacturers and players continues to follow, although these are already proving to be sub-optimal. The once selected bisonoric construction principle is no longer questioned. Alternative modifications of the keyboard system were made from the middle of the 19th century only on the basis of this principle, manufacturer-dependent and without a uniform standard. Rather various regional solutions for the most favourable grip options are developed in the search for keyboard layout, which are also reflected in corresponding designations: the Chemnitzer-, Carlsfelder- and Rheinische Tonlage (tone dispositon). These designate different spatial arrangements of the keys on the manual and the disposition of the tones. There is no connection on tone pitch. |

|

7. C.F. Zimmermann's Konzertina with oktave pressure from CarlsfeldCarl Friedrich Zimmermann's family moved from Morgenröthe to Carlsfeld in Saxony, not far away, in 1830. Zimmermann completed an apprenticeship in an iron foundry in Chemnitz, where he also met Uhlig and his Chemnitzer Concertina. According to his autobiography, after recognition for his playing of Uhlig's Concertina during a trading trip to Danzig, he came up with an idea: "I decided to build such an instrument myself, even larger, because Uhlig could not be persuaded to do so." Around 1843/44 he completed three such larger instruments with "many rows of keys". "Many rows" must therefore mean more rows than on Uhlig's Concertina. Consequently, Zimmermann had already built multi-row concertinas in 1843/44 in the same way as the instruments labelled bandonions from 1855 onwards. Because the external characteristic of the bandonion is that it has more than the three rows of Uhlig's Chemnitzer Concertina. In 1848, Zimmermann finally founded a concertina factory in Carlsfeld in the Erzgebirge in Saxony, where he built his own extended instruments following the example of Uhlig's Chemnitzer Concertina with slightly modified tone assignment. As early as 1849 he published an instruction for an instrument with 58 tones, of which no copy is known. The next edition with the title "Praktischer Selbstlehrer für Concertina" (Practical Self-Teacher for Concertina) followed for the London Industrial Exhibition in 1851 bilingual in English for up to 88 tones, and (presumably updated shortly thereafter) in German for 108 tones. The fingering tables contained therein describe a bandonion and are completely identical in tone assignment and key numbering to the instruments designated as bandonions from 1855 onwards and with Heinrich Band's "Practische(r) Schule für das 88 tönige Accordion" (Practical School for the 88-note Accordion) from 1850. If Zimmermann and Band sold Konzertinas with the same number of tones at the same time, but Band in his Krefeld music shop was demonstrably not able to mass-build instruments themselves, and no one else was making them at that time, then band must have sold instruments by Zimmermann. And already those that Band will later distribute as Bandonion. C.F. Zimmermann also introduced the 2-choir system called "octave pressure", which represents the decisive innovation for the sound of the bandonion and patented it in Saxony. (C.F. Buschmann had previously failed in Prussia because the patent office considered the principle to be known from organ building.) So the idea was not new, but Zimmermann established the characteristic, powerful sound of the bandonion with the first constructive implementation. However, presumably this led to a serious follow-up problem: According to Zimmermann's patent, the two choirs were not yet supplied with wind via a common tone hole with one valve, but each with its own tone hole and consequently two valves. Presumably due to the associated space requirements, the concept of multiple rows, i.e. an extension of the keyboard in horizontal expansion, was no longer feasible. Because Zimmermann returned to the three-row system, abandoning his logical key numbering. It is not yet possible to determine whether the changes that later led to the Carlsfeld system were made by Zimmermann or only under Ernst Louis Arnold. (for details, see in German Norbert Seidel) In 1864 Zimmermann sold his concertina factory to his foreman Ernst Louis Arnold and emigrated to his brother in the USA, took over his music shop in Philadelphia and later made the Autoharp (Accord Zither Harp) popular in the USA.

|

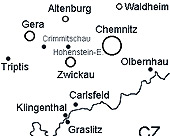

8. Heinrich Band in KrefeldHeinrich Band (1821-60) was one of the largest music dealers in the Prussian Rhineland at the time, with a shop in Krefeld opened in 1843. Band did not produce hand harmonicas, but bought instruments from manufacturers or had them built on his behalf. As late as 1855, he did not advertise concertinas such as those by C.F. Uhlig in Chemnitz and C.F. Zimmermann in Carlsfeld under their long-used name Concertina, but erroneously as Accordions, even though these single-tone instruments had no chord keys at all. A learning manual for Konzertina published by him this year is also still titled as an "Accordion" school. Afterwards, the Name Bandonion is verifiable. (This is the original spelling. Divergent came into circulation much later as export names.) The circumstances suggest that the name was intended to differentiate itself from other traders. The instruments sold by Heinrich Band were or corresponded to the early Chemnitzer Concertinas, to which he or his suppliers had change the numbering, tone assignment on some keys or added tone extensions, which is referred to as the Rhenish system. This "improved" keyboard system is identical to the 58-note Concertina by Carlsfeld manufacturer C.F. Zimmermann. A Bandonion is therefore a early Concertina by Zimmermann or a replica of him, to which Heinrich Band, as a dealer, had a Bandonion sign attached to it and possibly had tone changes and extensions made. The instruments that Band sold as Bandonion are not based on an own instrument draft or even an own invention. Neither descriptions nor patents from Band are known for this. In other words: Anyone who retunes a violin and adds two additional sides and a "Bandoline" sign has not invented a new instrument. A patent office would also confirm this. The basic prerequisite for the patentability of an invention is its novelty, which in the case of band is at best limited to the modification and extension of a keyboard. If Band's keyboard modifications were to constitute the invention of an instrument, as is assumed in some places, then all the developers of the many keyboard systems would each have invented an instrument. Based on the tone extensions, the model with 142 tones, the Tango bandonion and the Einheitsbandonion mit 144 tones are built. From 1924 onwards, the latter represented an attempt to unify the various bandonion systems, but this failed. All these models were manufactured by numerous instrument makers, mainly in Germany, who were not limited to one product, but produced concertinas, bandonions, mouth harmonicas and accordions according to demand. Through C.F. Uhlig's work, the industrial city of Chemnitz became the starting point for production. Subsequently, between Carlsfeld in the Erzgebirge and the neighbouring so-called Musikwinkel ("Music corner") around Klingenthal in the Vogtland in Saxony, the most important manufacturing region of concertinas and bandonions developed for many decades. To a lesser extent, production was also carried out by companies in Berlin, Gera, Bitterfeld, Magdeburg, Zwickau, Waldheim (Saxony), Munich, Vienna and other places. To whom does the Bandonion owe its existence? C.F. Uhlig developed the basic structure with a core keyboard, bisonoric construction and rectangular housing on his Chemnitzer Concertina as the archetype of all Deutschen Konzertinas. C.F. Zimmermann built Uhlig's Chemnitzer Concertina with an extended tone stock in more than three rows in a bandonion typical horizontal expansion as Carlsfelder Concertina. He had the idea for two choirs in octave tuning (like Buschmann), which gave his instruments the characteristically powerful sound of the later bandonion. Heinrich Band introduced the successful name Bandonion for marketing reasons and changed, extended the keyboard. Claims about the sole authorship of Band for the Rhenish keyboard system or even the entire instrument are not tenable. There is much to be said for a large share of C.F. Zimmermann from Carlsfeld. The later international fame of the Bandonion was ensured by the former two largest bandonion construction companies Alfred Arnold (AA) and Ernst Louis Arnold (ELA) in Carlsfeld in the Saxon Erzgebirge, which had emerged from Zimmermann's former concertina factory there. |

|

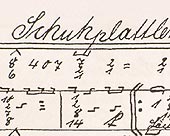

9. Music from the clothesline: The GriffschriftAs already explained, the concertina and bandonion developed with bisonoric tonal key dispositions. However, this does not follow a logical system. It is impossible to conclude from one key to the tone of an other key, because there are no regular, recurring tone intervals between the keys. Or in the words of C.F. Zimmermann from Carlsfeld, who seems to despair of his own work: "Consider the struggle with the notes for my first larger harmonicas: two different notes in tension and pressure on each key, the scala fragmented in its tone series by many rows of keys and possibly arranged according to accords. Even then, the key numbers / not tone numbers / had to glide over from this labyrinth and further and further away." (Autobiography) But how could such an instrument become a popular instrument? The solution of this riddle is the Griffschrift (grip writing or number notation). In order to be able to play in spite of the confusing tone arrangement and to provide a necessary orientation for learning the instrument, the keys have been numbered. The non-logical tone allocation of the keys was replaced by a logically arranged numbering system. These numbers have been written as so-called Griffschrift (number notation for the keys to be gripped) and are placed in front of the notes in the learning materials. Originally intended as a learning aid, however, the Griffschrift was soon transferred to all sheet music in general. Because with it the tones on the instrument could be found logically. And in order to acquire a playing skill, the learning of notation was no longer absolutely necessary. Even those unfamiliar with musical notation were able to find the right tone on the instrument. but also for musicians who played by notes it became tempting to play only by key numbers. In contrast to the disposition of notes to the keys, the key numbers are a system that can be understood on the instrument. Throughout his life, concertina maker C.F. Zimmermann was a concern to make it possible for amateurs without previous musical knowledge to make music with an instrument and promoted with great effort the use of Griffschrift: "34000 music books for accordeons and concertinas printed in numerals and all of them housed, which only slowly made the numerals popular with the audience..." (Autobiography) The usual notation of a piece of music was reduced by 1900 to such an extent, that only a line that "clothesline" was left over, on to which the numbers "hung". These have been supplemented by signs for the tone duration and necessary bellows direction. The enormous time saving for obtaining the playfulness had its downside of course. The most Konzertinas and bandonion players could not play by notes, but they needed the Griffschrift. This had to be appropriate for the type of instrument, so that the numbers corresponded to the keyboard used. For one piece of music there were therefore extra printouts for the Carlsfelder-, Chemnitzer- and Rheinische keyboard system (which are not all of them yet). But before all the simplest music theory education was impossible, because it is based on notes and not numbers. What may seem curious in retrospect made the Bandonion in Germany to a people's instrument. Only through the Griffschrift the Konzertina and bandonion achieved their broad effect, because it made the bisonoric principle spatially and logically controllable for the players. In addition, the Griffschrift also made it possible for those not familiar with music (and that was the vast majority) to play an instrument, the price of which (in contrast to a piano) was affordable for workers and small employees (if even under deprivation). It was the "little man's" piano, who not had the time by the long working hours and only one day off from work to learn a bisonoric instrument according notes as is still required today. One learned sequences of numbers instead of notes, because it was faster to reach the desired goal of making music in a bandonion club or family for fun and conviviality. Without the help of the Griffschrift, the bisonoric instruments would have not retained their wide range of distribution. Only this gave one actually difficult to learn and playable instrument a large group of buyers. Conversely, however, this means that its popularity depends above all on the acceptance of the Griffschrift. But this is completely useless for a music theoretical education. In the past, adults often acquired a bandonion, for whom was the quick acquisition of the ability to play in an association the focus. A deeper music education was mostly a privilege for children of wealthy parents who had the necessary money. Today music schools educate children from all walks of life. Parents expect their children to be educated not only in learning mere playing skills, but above all a music theoretical knowledge based on notes. With this claim is not more space for a note replacement like the Griffschrift. With the renunciation of this, the bisonoric Bandonion loses its makeshift, logical orientation system, without which the learning effort increases by a many times over. |

|

10. Why are there unisonoric instruments?An instrument in which the tone allocation of the keys is not affected by recurring relationships logically, but must be learned hard, is only by a small tone range easy to learn. The larger the range, the greater the learning effort. Four different tone dispositions (left, right for pull and push) must be learned. No two melodies are alike. Every chord grip, every inversion are unique for left, right and each bellows direction. Just to learn the tone allocation must be estimated at around 2 years. Logically structured manuals, on the other hand, allow not only the faster mastering of the tone allocation, but offer repetitive grip patterns and at best even fingerings (use of the same fingers) when playing. Time and energy of the learners do not have to use for a lengthy, mere tone orientation, but can be directed much earlier to the essential, the actual making of music. Just as the unisonoric principle became more and more established in accordion making, from 1900 there were also first attempts to build the Bandonion bisnoric and to equip it with a logical keyboard system. On other hand harmonicas, however, this was started much earlier. The English Concertina by dozens of British manufacturers has been built from the start since the 1830s unisonoric and with logical keyboard system. Around 1870 is the "Wiener chromatische Harmonika", later called Schrammelharmonika, verifable with a bisnoric and logical keyboard (B-grip). Their development may extend to 1854 back. It becomes the forerunner of all today's unisonoric accordions. 1891 Dr.med. Franz M. Gerl in Hindelang patented his single tone Handharmonium as unisonoric on both sides. In 1892 a unisonoric predecessor of the Symphonetta has been applied for a patent. An unisonoric bandonion was consequent. A corresponding keyboard system was designed by the multiple inventor Kaspar Wicky (1866-1917) and patented in 1896. With this unisonoric and chromatic system of whole-tone rows, he built his Schweizer Conzertina with four different tone supplies as a small concertina or in bandonion size. Wicky's system was independently invented a second time by Brian Hayden in 1963, patented in 1986 and still built in series as the Hayden-Duet (Concertina). 1903 Julius Zademack (1874-1941) presented another model in Germany, which however contained two different manuals. Their optimisation has been the subject of a constant tinkering, which 1925 flowed into the model Kusserow. In 1920 Hugo Stark (1873-1965) developed in Auerbach in the Vogtland his model Chromatiphon according to the unisonoric principle with logical keyboard system. From 1926 the company Schönherr u. Matthes (Olbernhau) built the model Praktikal. On both sides the 5-row C-grip system of the button accordion use, which 1996 from Norbert Gabla was taken up again in a different form in its development of his Hybridbandonions. For all these and many unnamed models, new manuals have been used, which were designed completely different from the bisonoric bandonions. Unisonoric instruments were also made by rebuilding the bisonoric bandonion. This happened to avoid a complex and expensive new construction and to be able to keep the size and construction of the instrument for tonal reasons. The unisonoric principle following each chamber had to be equipped with two equally tuned reeds. I.e. other reedplates are installed and if necessary, the soundpost should be adjusted. The latter because the shape and size of a chamber vary according to the reed inside it. In this way, an bisonoric model could be converted with a manageable modifications relatively inexpensive and with an timbre of a bisonoric instrument. Probably the most frequently used system in this way is the Péguri bandonion, developed around 1920 by Charles Péguri (1879-1930) in France. There were still many more designs, samples or small series, to make an unisonoric from a bisonoric bandonion by exchanging the reedplates and smaller modifications. (Lastly from 2007 with the model from A. Birken). In contrast to these ways, which keep the shape of the bisonoric manuals, for a different manual form not only exchanged reedplates, but the entire keyboard mechanics, soundposts, case frame etc. The whole instrument has to be redesigned, which naturally causes a considerable effort and cost as well as changes the sound. The price of such a prototype can correspond to that of ten instruments produced in series. |

Schweizer Conzertina by Kaspar Wicky...

|

11. Unisonoric bandonions - a short comparisonDecisive for the evaluation is the ergonomic playability, the logical order of the keyboard and design effort including resulting timbre. Meisel, Praktical, Chromatiphon and Péguri, all of which use the C/B grip of the button accordion have a more difficult way of playing. Because on the button accordion the hand is moved at an angle of 45° along up and down the manuals especially for melody playing, what is not possible with a fixed hand in a hand strap or thumb hole. Here must be played at an right angle to the manual alignment, which makes it difficult to play the melodyis with the C/B grip. This technical shortcoming is confirmed by the development of the Hybridbandonion where, to avoid this problem, the manuals are mounted at an angle at the front. There are no tight but wide hand straps, which extend over the entire height of the case as on an accordion and in which the hands can move more freely. The front manuals and wide hand straps require, especially when playing staccato, a greater dexterity and the lack of auxiliary rows a larger number of grip variants. The latter concerns also the Péguri, but where the C-grip is only part of the keyboard system. Praktikal, Meisel, Chromatiphon and also the Kusserow have been built for the additional space requirements of their auxiliary rows (16-25 keys on one side) mostly in slightly larger housings. This changes the timbre in comparison to the bisonoric bandonion. The Péguri, on the other hand, use the case of a bisonoric instrument therefore has no auxiliary rows. In the Kusserow, the mechanics of the auxiliary rows required complex sheet metal bending work, which could only be replaced in 2005 by Peter Spende with the installation of other key mechanic and under renunciation of an auxiliary row. This also made it possible to reduce the size of the housing. (However, Alfred Arnold already built Kusserows in the 1930s in the dimensions of bisonoric bandonions) In summary, it can be said that 'unisonoric' does not yet say anything about sound and technical quality. The Kusserow convinces with its constructional innovations of 2005 as an unisonoric bandonion type in playing technique and sonic. In 1927, the German Concertina and Bandonion Association voted it as the "most usable" of the unisonoric instruments. The ergonomically best solution of a continuous C/B grip on the Bandonion offers the Hybridbandonion. The Hayden Duet Concertina, based on the Wicky keyboard system, also deserves attention. With mirrored manuals and same tone direction, the learning effort could be reduced to the maximum. Unfortunately, this concept has only been implemented as a concertina, but never in bandonion size. |

|

12. Unisonoric or chromatic, diatonic or bisonoric?The superficial use of these terms are for laymens who are interested in hand harmonicas always a source of misunderstandings. Because often instead of 'unisonoric' the term 'chromatic' is used, and instead of 'bisonoric' 'diatonic'. But these are completely different facts. Chromatic and diatonic describe a musical aspect, the type of tone range of an instrument. In contrast, unisonoric and bisonoric are constructional conditional functional features: unisonoric means, one key makes the same ton on push and pull by two identically tuned reeds in a chamber; bisonoric, however, two differnet tones by two various tuned reeds. In contrast to this chromatic describes an instrument that has additional tones beyond a scale. With these the musical play can be 'colored' (Chroma = Color), in contrast to diatonic instruments (dia = passing through a scale), which can only be played over the the tones of one or more scales. The terms diatonic and chromatic describe the type of tones available in terms of the ton stock, but not their key disposition, whether the same or different tones sound on one key. For example with a chromatic instrument, chromatic (extended) tone sequences can be played, more as the 7 diatonic tones of a major or minor scale, which are only a part of the 12 tones of an octave. However, this can also be used for bisonoric intruments, as soon as its tone range has not only own tones of a scale, but also external tones. 'Full chromatic' means that as with the piano, each octave comprises 12 semitone steps, i.e. 12 tones without gaps. In contrast to the bisonoric, the unisonoric instruments were built fully chromatic from the beginning (English Concertina, Schrammelharmonika, Handharmonium, Symphonetta, Schweizer Conzertina), so that the (incorrect) equation of chromatic and unisonoric naturalized itself in linguistic usage. Since bisonoric instruments were built only with diatonic tone range for a long time, followed analogously the (incorrect) linguistic equation of diatonic and bisonoric. It is true that diatonic harmonicas are almost always built bisonoric, but for example the diatonic Russian hand harmonica Harmoshka is an unisonoric instrument. Conversely, for example, the bisonoric Einheitsbandonion is fully chromatic, i.e. not limited to the notes of any individual scales. |

|

13. Why of all things Bandonion?Each type of instrument has its own charms. In this treatise on the bandonion it is but allows its peculiarities to be emphasised. All squeezeboxes with their free reeds combine characteristics of completely different types of instruments. On the one hand, as with the piano, harpsichord and organ are played in several voices and the melody itself is accompanied harmoniously. Furthermore a dynamic sound design is possible, which can only be achieved with string and wind instruments. This squeezebox combination of polyphony, accompaniment and dynamic sound design is unique and represents both an opportunity and a challenge. This characteristics enable even a solo musician to give a filling performance. In contrast to the accordion, bandonion also have single tone systems on both sides, as C. F. Uhlig and C. Wheatstone had decided to build instruments without ready chords. Also the left hand should play single tones over the entire tone range of the left side. A standard bass accordion is content with less, which is, among other things, its wide range of distribution explained. In addition, the demanding bellows work must be mastered by one arm while at the Bandonion both are available and enable a more controlled (e.g. for tango sharper) bellows guidance. Furthermore the instrument can be play in a completely relaxed disposition. The arms are not subjected to strenuous playing dispositions because the instrument rests practically and comfortably on the thighs. The bandonion can produce a distinctive sound that is clearly distinguishable from the accordion. When the timbre of an accordion stroke the ears, like a cat cuddling around the legs, so the bandonion appear with more distance. Their sound has a certain effect more brittle, sharp and direct than the soft, pleasing accordion sound. However, the size of this difference depends on the type of bandonion is adapted to the preferences of the audience. The timbre is significantly influenced by the number of choirs and how they are tuned to each other. One-choir instruments can be good for aural training in children but they sounds 'naked' and are therefore unusual. Two choirs, on the other hand, have a sufficient base fullness. If not tuned to beat, they are clear, sharp and rich in contrast. In the higher tones they are almost shrill. Like a violin, its sound can pass through your bone and marrow or even tear the heart apart. Not for nothing this is the desired timbre of tango with its yearning tones full of unfulfilled hope and disappointed love, as it is sung about in the lyrics of tango music - melancholic, sad or quick-tempered and love-mad. In short: Tango is not music that makes you slap your thighs in joy, as is the case with polka or Schuhplattler. In contrast to the Tango, the latter were preferably played in former times especially in Southern Germany with choirs tuned to beat slightly different. The unisonoric bandonion by Charles Péguri was mostly tuned to beat for the French Musette. But a tuned beat is not compatible with classical music or the strongly rhythmic of tango with its characteristic intermittent playing (staccato). However, a bandonion should not be judged by whether sounds with or without tuned beat. Rather, the question arises whether a beat to the music being played fits. But tuned beat is waived (as is generally usual today), then a bandonion unfolds its unique timbre most clearly. On instruments where more than two choirs sound together, this is lost again a little bit, because the timbre will softer, more organ-like, more blurred, which is further intensified by a beat. That is why such instruments are mostly used solo or only in small formations, because it is difficult to assert themselves in larger chapels due to the lack of sound contrast. Besides the unmistakable timbre of a bandonion, there are two non-musical aspects mentioned: its size and weight. A bandonion is easy to transport. Who was allowed to carry a a standard bass accordion with 96 or even 120 basses, will be able to weight the luxury of a instruments in suitcase size, especially with this single tone instrument potentially more is possible. Single tone accordions also offer these possibilities, but require with the most common converter models an additional weight in mechanics and a significant larger housing. How does this relate to your own musical and tonal ideas, everyone has to weigh up for themselves. |

14. What influences the sound of the Konzertina and Bandonion?The sound and its volume are produced by the free reed. It interrupts the wind from the bellows at its reedplate channel at its natural frequency, which causes the air to vibrate and is audible as airborne sound (tone). This airborne sound also causes the bandonion housing and its internal parts to vibrate. However, the sound radiation from the case to the outside is much quieter (around -30dB; IfM 128) as the sound of the reed escaping at the tone hole of the open valve. Most of the sound of the reed reaches the outside from the tone hole through the openings on the sides of the case. (Structure-borne sound transmission from the reeds to housing parts, i.e. via the material rather than the air, is detectable but insignificant). The reeds of the bandonion produce the final volume themselves. This is not the case with piano strings and string/plucked instruments (with the exception of the harp). They only produce a low volume, which has to be amplified by a soundboard. For example, the vibrations of a piano string are transmitted as structure-borne sound via the bridge to a large soundboard, which can cause a lot of air to vibrate and thus act as an amplifier. Without this, a piano would be like a guitar without a body. The sound of a bandonion is mainly determined by the characteristics of the free reeds and reedplates. To a much lesser extent, the dimensions and workmanship of the other parts and materials also influence the frequency spectrum of the overall sound, which is referred to as tone colour. It does not matter whether the instrument has a bisonoric or unisonoric tone assignment. If a bandonion type is built with an identical design and manufacture, once with a bisonoric and once with an unisonoric tone system, there is no difference in sound colour, even if this is sometimes assumed. A corresponding argument is that different reeds are arranged next to each other on the reedplates depending on the type of tone assignment. This would result in a different resonance behaviour of the reeds and thus, for example, a special sound of the (142-tone) bisonoric bandonion compared to an unisonoric. This assumption presupposes a reed resonance caused by airborne or structure-borne sound transmission, comparable to the string resonance on the piano, by which unstruck strings can resonate with struck strings. However, no evidence of such an effect between the reeds on the bandonion is known to date. Even assuming a reed resonance, the sound radiation (volume) of a reed that only resonates, i.e. is excited without bellows wind, would be far too low to be able to influence the sound. Audible sound radiation requires wind that is periodically interrupted by a reed and flows through the open valve. If, on the other hand, a reed is plucked mechanically without wind only a minimal buzzing sound is produced. In addition, any reed resonance would be triggered by airborne sound, for which the allocation of the reeds on the reedplates would be irrelevant. (Structure-borne sound transmission via the rivet of a reed to the reedplate is only of secondary importance (IfM 138). The assumption of a reed resonance influencing the sound, from which a special tonal position of the bisonoric tone principle is derived, cannot be physically proven and cannot be reproduced on the tuning table. (Such an effect is also not known on the accordion and mouth harmonica.) Differences in sound between bandonions result solely from the material, construction and production by different manufacturers, but not as a result of the bisonoric or unisonoric tone principle. If a certain bandonion sound is favoured, such as that of the 142-note bandonion in tango music, then this is the result of the bandonion makers manufacturing skills. There is a reason why Argentina's bandonion fans were moulded by the sound of this one model for decades: tens of thousands of similar instruments were supplied by just one manufacturer - Alfred Arnold's bandonion factory in Carlsfeld. The material and production of one manufacturer with consistent quality led to a recognisable sound. For this reason, in Argentinian tango music the 142-note bandonions from other manufacturers with a different sound were quickly recognised and rejected, as bandonion makers can tell in detail.

|

One manufacturer,

|

15. Bandonion? What is that? Questions of todayThis question may sound exaggerated, but unfortunately it is the result of many everyday experiences. In Germany only a few people can still associate a concrete idea with the term bandonion. In one area of course this does not apply - that of tango music. The bandonion lives and is at its centre and symbolises them. Diverse national and international activities reach a large circle of tango lovers. The Tango music has been saved the instrument over the last decades and mainly through the tango music it still experiences a noteworthy public perception. This is a good thing, but it also has its downside. The bandonion is perceived, if at all, as a pure tango instrument. Only a few people still know about its use beyond this area. It disappears, as it were in a Drawer. An interest in the instrument stands or falls often with the personal attitude towards Tango music. But to limit the bandonion to tango does not do justice to its manifold possibilities of playing and expression. With the playful possibilities of a piano certainly comparable, it can be used in the most diverse musical styles. Classical piano and Organ works can be a rich field of activity for bandonion players. Representative of this field is Rene Marino Rivero (Uruguay) with its classical repertoire. Dino Saluzzi (Argentina) even demonstrates the diversity of the instrument in the field of jazz. At Per Arne Glorvigen from Norway, the complete musical breadth of bellows can be experienced. And the traditional possibilities in the folk and Entertainment music goes without saying. A large and grateful audience would find at Folk festivals, in beer gardens, while hiking, as well as at events with family and friends. Just - the instrument is (at least in Germany) hardly audible anymore. Apart from the lower presence of amateur music at all in comparison to the earlier, which is largely due to today's technical world, the question arises as to the reasons for the absence of the Bandonions in Germany. Why is an instrument that was once an integral part of everyday culture in Germany almost unknown and hardly to be found? There are several reasons for this. The first incision brought the mass introduction of the much easier to learn unisonoric piano accordions around 1930, which the confusing multitude of various concertina and bandonion models opposite. Also with the intensified turn to musical notation, the difficult learnable bisonoric instruments lost their acceptance. Furthermore from 1920 changed the taste of music lasting through the influences of jazz. At the time, jazz was considered to be light music characterised by the USA with new fashionable dances such as the Foxtrot, Charleston, Shimmy, Slow Fox etc. The accordion was seen as an instrument of this jazz music. The decision between piano accordion and bandonion thus also became a question of modernity and generations. However, special consideration must be given to that bandonion music in Germany was primarily club music. The Bandonion clubs were the relevant places for the dissemination of the instrument. But they served not only the musical purpose, but also always fulfilled a social one. The former variety of concertina and bandonion player is not only explained by the instrument, the musical aspect, but also by the social function of the associations among workers, small businesses and simple employees. In their decision for this instrument, not only musical ideas, but often the social environment is decisive. No matter how the weighting between musical demands and social gathering in the individual clubs may have been, the clubs formed the existential framework for the wide dissemination of the instrument (see Graf). Most of them, however, with their adherence to the Griffschrift, the often missing knowledge of music theory and due their age structure were neither able nor willing to open up to new ideas. They embodied with their mainly from the imperial period play goods no modernity in these times of rapid technological, cultural and political changes. This could not remain without consequences for the public perception of the instrument and the recruitment of young talents. The 1924 established nationwide organisational structure of the bandonion movement broke up again after 10 years also as a result of these contrasts. The Second World War, which soon followed, also tore many gaps in the local music clubs. The close connection between bandonion clubs and the spread of the instrument had led to the consequence that a decline in the number of clubs was also associated with a decline in the number of instruments. In addition to the dwindling number of clubs, the effects of the war also caused the end of the production structures of manufacturers whose main centres were now located in the Soviet occupation zone. As a result of the expropriations there, many company owners and production managers moved to the West Germany, while the highly specialised workforce was left behind in the East. Both could not really replace the missing part. But apart from these factors of the instrument's environment, the reasons for today's low use of the bandonion must also be sought in the instrument itself. Because Klingenthal and Carlsfeld remain in the GDR production centres of the instrument industry. The bandonion production will soon be discontinued - in favour of the accordion. The VEB Klingenthaler Harmonikawerke supplied large parts of Eastern Europe with Weltmeister accordions. With corresponding demand, the bandonion in the GDR could also have been built further. But this demand was no more. This was not only the case for manufacturers in the East, where demand was not necessarily a mandatory criterion for the planned economy, but also those in West Germany and West Berlin. At the end of the 1960s the bandonion production had come to a standstill. A first revival was carried out by Klaus Gutjahr in West Berlin, who produced in 1976 a further developed bisonoric bandonion in his own construction and has made many improvements to the 142-tone and Unit Bandonion over the years. |

16. From high into lowWith concertina and bandonion it was possible to quickly get to playing practice, if the numbering of the keys and the fingering based on them. This was until the 1930s the Standard with the bisonoric bandonion. Note players were the exception. The Griffschrift was the logical makeshift system of the bisonoric instruments, such as tabulator still make playing the guitar easier today. With the increasing turn towards playing by notes even in the layman's area and the associated turning away from the Griffschrift, the very high learning effort of a bisonoric keyboard comes to light. Instruments are often recommended and a difficult to learn is not good advertising. This may not be a good argument under musical aspects, but for the distribution of an instrument this is a decisive factor besides the price. But although there were also easier to learn unisonoric instruments from 1925 onwards, also these are no longer present. Their development came probably too late, because around 1930 the marketing of the Standard bass accordion was already at full speed, as a result of which the bandonion is strongly lost acceptance. Whoever felt obliged to playing by notes, resorted to the general fashion following rather to the accordion, than to rack their brains ober the existence of a new unisonoric bandonion type. The time for the unisonoric bandonion was much too short, as that it could have established itself as an alternative to the bisonorics and possibly can uncouple from its incipient decline. Due the much lower production figures of unisonoric instruments, there is no corresponding second-hand market with affordable offers for beginners today. With new-prices from 5.500 Euro, this is also a considerable obstacle for the distribution of a musically potent instrument. The new companies of bandonion construction, wich were founded in Saxony since 1990 continued there due to market conditions, where in the 1940s the former end point was reached - at the Tango market with its traditional focus on bisonoric instruments. Another market, such as folk and entertainment music, no longer existed for the bandonion around 1990. Already in the 1930s, the tango market brought the company Alfred & Arnold a production high. Over 30.000 instruments were exported to Argentina, while at the same time, sales in Germany were already declining. The tango musicians were a welcome market, which made them the focus of interest for manufacturers and distributors - until today. A subjective view Tango bandonionists are usually professional musicians with the practice time and playing practice necessary for an bisonoric instrument, which professional amateur players do not have. And almost all tango musicians present the bisonoric 142-tone bandonion as an ideal sound. The sound concepts of tango music thus become the general standard for the instrument, which is also followed by the few manufacturers with their offerings. Instead of bringing a playable and tonally usable unisonoric instrument to product maturity and advertising it, the main aim of the manufacturers is to copy the sound of Arnold's tango bandonion. The highest recognition goes to those who succeed. But what use is this undoubtedly extraordinary technical achievement if this bisonoric instrument is only orientated towards the limited demand for tango music? If this remains the claim, there is no need to complain about the imminent "death" of the instrument (note below). It is not possible for interested parties without knowledge of the instrument to critically survey or even question these settings. Throughout his life, it was C.F. Zimmermann's concern to provide the many (potential) amateur musicians with an easy to play instrument. His remedy for this was the key numbering and the Griffschrift based on it. His claim for today would be to make visible and available again a quickly learnable unisonric bandonion, such as the Kusserow, which Peter Spende significantly improved around 2005. Alfred Arnold recognized the business opportunities for the bisonoric Tango bandonion in Argentina. Who recognises them today in the potential customers of useful unisonric instruments, and thus perhaps helps the instrument to blossom again, i.e. to have a broad impact beyond the limited regional tradition? On the other hand, with the continued promotion of the difficult to learn bisonoric bandonion by music teachers and manufacturers, many interested parties are likely to spoil the path to the instrument that they might take with an unisonoric model and a logical keyboard. Anyone who wants to experience tango with a 142-tones bisonoric bandonion can do so at any time. But a bandonion can play more than tango. Which is why the approach of trying to stop the decline of the instrument by declaring tango a world cultural heritage seems questionable. Because the real shortcoming is the low usage beyond tango music, with exception of a few regional centres. (Quite apart that frail patients rarely regain vitality through artificial respiration - most of the time the opposite occurs.) The last 30 years have shown that with the dominating advertising of bisonoric instruments, the interest in playing the bandonion has not increased. Not to mention hearing and seeing them again in everyday life. Note Carla Algeri, UNESCO Commissioner for the Preservation of Tango, Argentina, complains with the following invocation: "Dear Bandoneón, tell me Bandoneón, what should we do so that you do not continue to die?" (Buenos Aires, 11.7.2020) Perhaps part of a possible answer lies in the following anecdote: Completely ignorant of the Bandonion, I was looking for clarifying information on the net in 2009, but it was only very scattered. The name Oriwohl often appeared, somewhere with a Berlin telephone number. However, the year of birth 1916 gave little hope of information, because he would have to be over 90. But someone picked it up, and it was Karl Oriwohl. I told him about my interest in the bandonion and whether he could recommend one of the many types of bandonion to me, an overwhelmed layman by the question of instruments but interested beginner? The first sentence I heard from him was: "If I can give you one piece of advice, don't choose an bisonoric instrument..." |

Hints of all kinds gratefully requested: post@bandonioninfo.de Sources:

|

chin. Mouth organ Sheng, (H: 60cm)

chin. Mouth organ Sheng, (H: 60cm) Foot of a Sheng pipe with a free reed

Foot of a Sheng pipe with a free reed Portatives were portable pipe instruments according to their name and were used as well as regals with a bellows ventilated....

Portatives were portable pipe instruments according to their name and were used as well as regals with a bellows ventilated.... A regal of the end of the 16th century with beating reeds

A regal of the end of the 16th century with beating reeds Playing disposition on a Physharmonika...

Playing disposition on a Physharmonika... Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann (1805-64).

Christian Friedrich Ludwig Buschmann (1805-64). The asymmetrically attached reed of a mélophone....

The asymmetrically attached reed of a mélophone.... Accordion with one manual. Start of development of all hand harmonicas.

Accordion with one manual. Start of development of all hand harmonicas. This flat design of chambers is called in german flat or board chamber...

This flat design of chambers is called in german flat or board chamber... The reedplate and 10 reeds cover the chambers for five keys of a very early concertina....

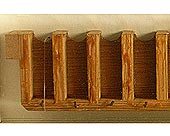

The reedplate and 10 reeds cover the chambers for five keys of a very early concertina.... An upright group of chambers on the mounting floor is called a sound post...

An upright group of chambers on the mounting floor is called a sound post... English Concertina by Wheatstone from London with the case cover removed. Characteristic is the hexagonal construction. Also the inner construction is fundamentally different to the Deutsche Konzertina.

English Concertina by Wheatstone from London with the case cover removed. Characteristic is the hexagonal construction. Also the inner construction is fundamentally different to the Deutsche Konzertina. A Concertina with 76 tones from the factory of C.F. Uhlig in Chemnitz

(before 1874)

A Concertina with 76 tones from the factory of C.F. Uhlig in Chemnitz

(before 1874) Repeat tones on the manual of a Konzertina...

Repeat tones on the manual of a Konzertina... The typical vertical extension of a Konzertina keyboard. Here the example of the Chemnitzer

keyboard system for 100 tones.

The typical vertical extension of a Konzertina keyboard. Here the example of the Chemnitzer

keyboard system for 100 tones. The mainly horizontal extension of a bandonion manual. These 6 rows are

is based on the Rhenish keyboard system. Shown here on the 142-tone bandonion.

The mainly horizontal extension of a bandonion manual. These 6 rows are

is based on the Rhenish keyboard system. Shown here on the 142-tone bandonion. Production facilities in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century

Production facilities in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century There are no notes here. What for, most people said to themselves, if it is easier with numbers

goes. Due to this long and widespread playing practice, in Germany a bisonoric instrument were also

called number bandonion. The Griffschrift (tabulator) are also used for bisonoric accordions and the guitar.

There are no notes here. What for, most people said to themselves, if it is easier with numbers

goes. Due to this long and widespread playing practice, in Germany a bisonoric instrument were also

called number bandonion. The Griffschrift (tabulator) are also used for bisonoric accordions and the guitar.  "The C major scale is ..., try playing by notes and maybe learn it"...

"The C major scale is ..., try playing by notes and maybe learn it"... Section of a keyboard with key numbering

Section of a keyboard with key numbering Symphonetta, musical summit performances...

Symphonetta, musical summit performances...

Handharmonium patented in 1891

Handharmonium patented in 1891 A first unisonoric model from Julius Zademack from 1911...

A first unisonoric model from Julius Zademack from 1911... 1. Chromatisches Bandonionorchester Berlin around 1910...

1. Chromatisches Bandonionorchester Berlin around 1910... Unisonoric Péguri bandonion...

Unisonoric Péguri bandonion... Praktical with C-grip and thumb hole

Praktical with C-grip and thumb hole Hybridbandonion...

Hybridbandonion... Bandonion course, music school F. Hensel, Berlin...

Bandonion course, music school F. Hensel, Berlin...

Harmoschka from Russia: diatonic and unisonoric...

Harmoschka from Russia: diatonic and unisonoric... Kusserow: chromatic and unisonoric (Spielanleitung youtube)...

Kusserow: chromatic and unisonoric (Spielanleitung youtube)... Einheitsbandonion: chromatic and bisonoric...

Einheitsbandonion: chromatic and bisonoric... Gran Orquestra Carambolage (founded 2011) from Germany, Direction: Jürgen Karthe (left)

Gran Orquestra Carambolage (founded 2011) from Germany, Direction: Jürgen Karthe (left) Particularly popular in Southern Germany - the tuned beat. Probably also among The Marquartsteiner...

Particularly popular in Southern Germany - the tuned beat. Probably also among The Marquartsteiner...

Florecia Amengual.

Florecia Amengual. At the headquarters of Uhlig's Deutsche Konzertina in Chemnitz, there has been a bandonion course with Jürgen Karthe at the Municipal Music School since 2020

At the headquarters of Uhlig's Deutsche Konzertina in Chemnitz, there has been a bandonion course with Jürgen Karthe at the Municipal Music School since 2020 Process for the production of free reeds up to the quality company Dix in Gera (Thuringia)

Process for the production of free reeds up to the quality company Dix in Gera (Thuringia) AA, 142 tones, unisonoric,

AA, 142 tones, unisonoric,  Jazz - in Poland, where else?

Dino Saluzzi and son at the Festiwal Jazz na Starówce in 2008 (youtube.com)

Jazz - in Poland, where else?

Dino Saluzzi and son at the Festiwal Jazz na Starówce in 2008 (youtube.com) Per Arne Glorvigen from Norway... (youtube.com)

Per Arne Glorvigen from Norway... (youtube.com) Who still wants to play bandonion at this sight? Besides the easier learning and playing

also the marketing of the company Hohner provided for the rapid spreading of the piano accordion.

Compared to the bandonion it embodied modernity...

Who still wants to play bandonion at this sight? Besides the easier learning and playing

also the marketing of the company Hohner provided for the rapid spreading of the piano accordion.

Compared to the bandonion it embodied modernity... The youth reaches for the piano accordion. On the other hand, the Bandonion loses quite quickly

importance measured by its former distribution during his great time from 1900-1930...

The youth reaches for the piano accordion. On the other hand, the Bandonion loses quite quickly

importance measured by its former distribution during his great time from 1900-1930...