Concertina and Bandonion Clubs

Chapels and Orchestras

Between artistic aspirations and social gatheringsThe first clubs can be traced back to 1870. After 1890 they experienced a strong boom and by 1900 there were at least 75. After that, the bandonion movement became a mass phenomenon in various regions. In many large German cities, especially in Saxony, there were one, sometimes several, clubs in every district. In 1938 there were 686 clubs (Graf 161).

Mostly in club rooms of pubs, even beginners practiced right away practically on program pieces in order to be able to present a club result as quickly as possible. And then it was time to take to the streets, especially since the clubs were often rooted in the working-class milieu. (Photo: presumably Konzertina stronghold Chemnitz)

Open-air parades often took the form of a musical procession.

Clubs were then loud and strong, even on small village streets. Sometimes led by a lyre, a metal plate game with mallets from military music, which often set the stylistic tone in the form of marching music.

The enthusiasm and the mass character can also be explained by the fact that until the 1920s, musical needs were not yet satisfied by an omnipresent radio, but (apart from gramophones and music machines) music always represented a special, public and handmade experience, for which real musicians were needed.

Clubs also formed associations, the largest of which was the Deutsche Konzertina- und Bandonionbund (DKuBB, 1911-35).

Unmistakably, this is a Konzertina and bandonion club with accompanying instruments.

Here, too, there is a lyre, ideally suited for tonal embellishments, which bandonion players usually did not see as their task.

In contrast to the authoritarian governance of the German Empire, association structures were also a school of democratic co-determination, which was later incorporated into the Weimar Constitution.

Players and clubs exchanged information mainly through trade journals, the most important of which was Gut Ton (GT) from a Dresden publishing house with 30 years of printing (1910-40). Until 1924 it functioned as the official organ of the DKuBB, before the latter started its own club newspaper Die Volksmusik (DV) due to differences.

DKuBB with DV disbanded in 1935 as a result of the Nazis' conformity of the music area.

Im Wald und auf der Heide, / In the forest and on the heath,

da such ich meine Freude... / I'm looking for my joy

Also in mixed chapels often present several times - Konzertina and Bandonion. And in such chapels it is certainly one of the most appealing in terms of sound.

Konzertina and bandonion players, however, were usually not looking for mixed chapels, but rather a group-oriented club with its peers. At that time, it was mainly adults who were already learning to play the instruments, for which the clubs offered themselves as the first port of call, especially since they played there as one among many. Mixed chapels, on the other hand, required individual musical knowledge and skills.

The essence of a Konzertina and bandonion club as a meeting place for like-minded people usually led to a formation of many Koncertinas/Bandonions and, if at all, only one or three other instruments.

Then Konzertinas/Bandonions, one violine.

Konzertina and Bandonion are melody and accompaniment in one, so they can be self-sufficient when playing. There is not necessarily the compulsion to include other instruments, which then leads to a pure Konzertina/Bandonion orchestra.

If, due to a lack of orchestral skills and knowledge of notes, the first melody part plus chords is always played, the term "orchestra" as the multiple instrumentation of individual voices is misguided. Playing only one voice with instruments that were often tuned to beat at that time could quickly lead to a mush of sound.

In 1925, Walter Pörschmann complained: "From a musical point of view, it is now absurd to hear one and the same melody from 10, 20 or even more bandonions."

In 1928, therefore, efforts were intensified to "bring Konzertina and bandonion music to an orchestral basis" so that "we can finally get out of this eternal, monotonous dilemma." (DV 1925/100)

E. Kusserow also stated: It is not much fun when "when listening to a bandonion concerto, that indefinable murmur arises at the place of the accompaniment, above which the melody is then enthroned high up without any middle register." (DV 1928/53 beides Graf 229)

He recommended: "Out of every four players, one can confidently only bring forward and follow-up. (...) A second bandonion (conceived as a quartet) would have to bring mainly cello solos and play the second violin part on the right. The third bandonion will be particularly interested in the voices of the woodwinds, and only one instrument will take over the melody." (DV 1928/37)

Foto: "Volksmusik-Vereinigung Morgenroth, Hannover 20.7.32"

A divided bandonion playing was hardly common. And this until well into the middle of the 20th century, as the following lines from Halle still show for 1965:

"With his [new orchestra leader] we took an upswing, which mainly affected our pieces, but also the way we played. In the past, everyone played the same voice. Now we played polyphonically."

The sound of the adjacent orchestra has not been preserved, but the instrumentation is promising: 11 bandonion players with a centrally presented cellist, three double bass players and 21 strings...

Efforts to improve orchestration came from associations such as the DKuBB, but achieved little success. They failed due to a lack of musical skills or a lack of interest in recommended pieces of music as a result of the beginning of the aging of the clubs.

The problem with unison bandonion orchestras is the lack of clear coverage of different parts of the voice. A brass band can easily do this with tuba, clarinet, flute, horns, etc., even if it should consist only of wind instruments in unison. This don't necessarily need double bass and violin as a striking addition. This is not equally feasible with Konzertina and Bandonion alone.

It is no coincidence that, as for later accordion orchestras, extra instruments such as a bass and piccolo bandonion were developed to remedy this orchestral deficiency due to the lack of other instruments. In the case of piccolo bandonion, the question arises as to why a chromatic Duet Concertina was not considered for high passages.

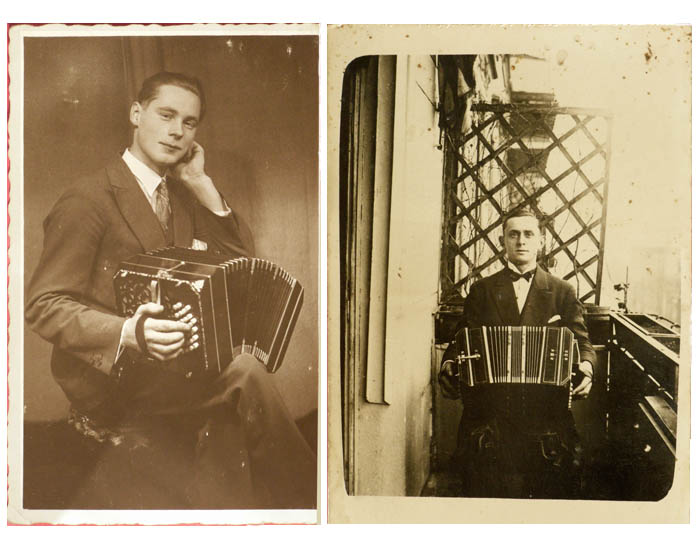

Pictured: For ambitious soloists, questions about orchestration cannot arouse any real interest.

In the recognizable field of tension of an association between the need for convivial pleasure with a hearty beer on the one hand and an artistic claim underlined with tie and bow tie on the other.

What could cause discomfort or even pain to the trained ear of the professional musician is accepted calmly by the amateur musician with a shrug of the shoulders. He knows the strengths and weaknesses of his own playing, without the latter being able to discourage him. Because he is not looking for perfection, but harmony with like-minded people in conversations, in the exchange of news, well-intoned jokes and cold beer. And when the tempo, rhythm and assignments are right when making music, everything together fills him with joyful gratitude.

Whistling a melody, he then happily moves homewards.